The Legend of Education

I come from a generation that has grown up with video games. And I'll preempt any disgust with a disclaimer that I prefer games that emphasize creativity and immersive design over violence. However, I'll admit, the two are not mutually exclusive. I've often wondered when videogaming would, in earnest, embed itself into literary criticism and education. Sure there have been tinkerers, and dissertations, but a discussion published in September's Harper's Magazine (sorry no link without a library subscription) titled "Grand Theft Education" reveals what has attracted so many of my generation to video games.

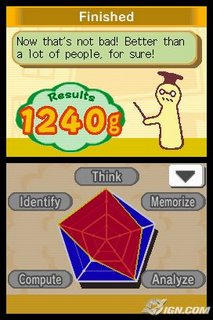

For their part, most good video games (and there are more bad ones than good ones) require players to master certain skills, skills players may not realize they are mastering, like spacial relationships, memory assignment, and accurate timing. Video games encourage us to figure out the rules of the game and then tweak how we play to improve nearly without end.

The promise for gaming and education lies in a simple idea, an idea video game designer Raph Koster suggests by quoting Mark Twain. "Work consists of whatever a body is obliged to do. Play consists of whatever a body is not obliged to do." The beauty of games, video games in particular, is that there are no explicit consequences from winning or losing. Koster argues that it's okay to fail in video games, and that a problem with standard pedagogy is that "it all matters too much, there's pressure to succeed. And that turns off a lot of learners." Devouring a novel cover to cover for a class by decoding every ounce of irony, pouring over every plot element, and revealing all of a character's humanity can leave a lot of learners with a sterile imprint of a masterpiece.

In terms of pedagogy, the use of classroom games are valuable. I believe great potential exists for teachers and learners to tap into video games and help to alter the gaming landscape currently strewn with hyper-violent games. Gaming trends are ripe for change, especially with the success of recent games like Big Brain Academy and Nintendogs for Nintendo's DS platform and a soon-to-be released Wii platform touting gaming for the masses. Classroom applications could aid this trend towards games that encourage the types of literacy skills all students need for instance.

The Harper's discussion describes an application that would resemble wikipedia and allow students to perfect a writing assignment together. Students would receive points for improvements they make to the writing and those points could be accumulated as pride points. The article goes on to suggest play and games are having an impact on how we learn and how we create--a very democratizing effect.

For me the takeaway of the article is in the type of literacy we should be teaching, and gaming's impact on current literacy. There are no easy answers here, but clearly our contemproary media are written and performed a lot differently than Victorian era media. The suggestion that great challenges exist for teachers in an age where so many literacies are accepted and promulgated should raise cause for alarm. A lot of kids don't understand what we are teaching them when it comes to literacy because the way we teach it is unidentifiable with their lives.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home